IN HER new film, the fantasy epic Snow White and the Huntsman, Kristen Stewart plays a young princess who escapes deprivation and confinement, survives testing trials and acquits herself as a leader ready to claim what is rightfully hers. The story is derived from a Brothers Grimm fairytale, but it has no shortage of contemporary relevance, especially for the American actress.

''She's been imprisoned by Twilight and this is her breakout,'' says Rupert Sanders, the British director making his first feature with Snow White and the Huntsman. ''Kristen's very talented and she's got a huge career ahead of her where she will constantly surprise people.''

As one of the few successful child actors to transition without a hitch into adult roles, Stewart feels like a familiar screen fixture despite being merely 22 years old. She was just 17 when she was cast as Bella Swan, the chaste teenage girl who falls in love with Robert Pattinson's brooding vampire in 2008's Twilight. That overwrought franchise finally ends this November, and it appears that while she's grateful for the exposure, Stewart is ready for the next phase of her career.

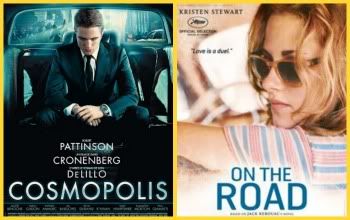

''I'm not trying to distance myself from Twilight, but there are several films coming out this year that are going to compound the sense of change,'' Stewart says. ''I've done things that are far and away from anything I could imagine, and right now I'm bursting with emotions and questions.''

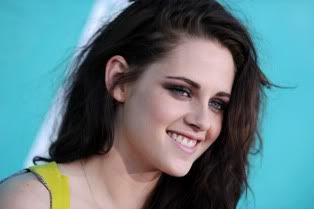

The media image of Stewart established through the various Twilight cycles is that of an uncommunicative young woman alternating between disdain and boredom in her promotional appearances. However, on a quick visit to Australia with Snow White co-star and former Phillip Island lad, Thor lead Chris Hemsworth, she spoke in swift, excitable sentences and referred to roles in films she believed in as ''causes''. Stewart repeatedly used ''tactful'' in a pejorative sense, as if it was plainly preferable to shake things up.

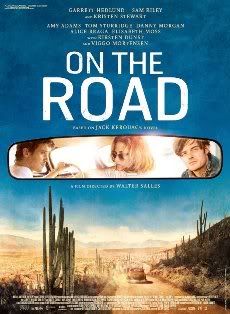

Stewart was widely praised at the recent Cannes film festival for her turn as the libidinous, forthright Marylou in Walter Salles' adaptation of Jack Kerouac's seminal Beat-era text On the Road, but right now it is Snow White and the Huntsman that is fortifying her commercial leverage. Sanders' film has quickly earned more than $250 million overseas in a season where several expensive blockbusters, such as Battleship, have failed commercially.

The revised storyline, rich with bloody ill-doing and tactile physical textures, has Charlize Theron as the evil queen, Ravenna, who literally kills young women for their youth, and needs to recapture the stepdaughter she locked away when she killed the girl's father. In a landscape alternately bleak and idyllic, Ravenna's unwilling agent is Hemsworth's widowed Huntsman. In this swords-and-spells edition there are seven dwarves, but they definitely do not sing.

''Our take on the whole idea of a fairytale is very elemental,'' says Sanders, a graduate of television commercials, who delivered the film on a painfully tight schedule to meet the studio's pre-ordained release date. ''But the fact that we've got two strong women playing masculine roles is very modern, and that's part of what excited me.''

The movie's take on femininity feels connected to a 21st-century world view, suggesting that in a world where men expect to rule, women will turn on each other in a bid to prosper. Ravenna's hunger to destroy Snow White could apply to the corporate world or to Hollywood, where female stars have narrower windows of opportunity than their male counterparts.

''I think that the reason the story has never been irrelevant is that it's so fundamental: you have to have heart,'' Stewart says. ''I've met so many people who've become so ugly, people that I thought were really beautiful, because they don't come from anywhere apart from the purely superficial. What they do doesn't work and it doesn't move you. Women can see that, and they can sense it.''

Sanders saw the possibilities in the respective roles for Theron and Stewart early on. The former, he says, had a beauty and a strength she was willing to turn into something destructive, while the latter has a rebellious streak struggling to get out from under the weight of the world on her young shoulders.

''Sometimes you have qualities that you don't know about until you meet someone, or read something, or hear about a story and you realise, 'Wow, that's scary and it speaks to me, I should do that,''' Stewart says. ''Rupert presented a world I wanted to live in and so I believed in the cause.''

Unlike some of her contemporaries, who are adept at promoting themselves but are workmanlike on the screen, Stewart struggles to banter with David Letterman but excels at playing someone else. In close-up, the most technically demanding camera set-up for an actor, she can convey complex emotions without saying a word. That's a blessing and a curse, but she's now completely comfortable with that.

''I love close-ups,'' she says. ''I've never done theatre and although I started at a young age, I was never the kid in the middle of the room. I was never a performer. When there's a camera in my face there's just no going back, there's no excuse. It's better for me because as soon as you pull the camera back there are one hundred walls I can get behind. With a close-up, you can't hide.''

@mel452 fiercebitchstew